Long-standing Bumiputra policy favors ethnic majority, from scholarships to contracts

KUALA LUMPUR (August 20): Prime Minister Mahathir Mohamad’s hand-picked advisers have recommended changes to Malaysia’s Bumiputra policy, a set of affirmative action measures designed to lift the social welfare of the majority ethnic Malays. The policy, introduced in 1971, grants a wide range of privileges — from scholarships to access to government contracts — based on ethnicity rather than merit.

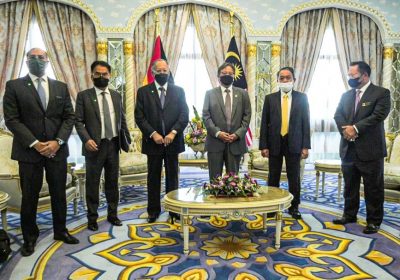

Figure 1: Daim Zainuddin, head of the Council of Eminent Persons, speaks to the press in Kuala Lumpur on Aug. 20.

Past attempts to revise the policy have been met with strong protests from conservatives, including Mahathir, who argued that Malays would be diminished in their own birthplace without state support.

According to a statement from the Council of Eminent Persons, the Bumiputera agenda is to be looked at from the view of enhancing Malaysians’ socioeconomic well-being.

“We want to get it right this time,” council head Daim Zainuddin told reporters on Monday. The former finance minister did not reveal the recommendations but said the advisory council would induce a “positive mindset change” of the Bumiputra community geared toward competitiveness.

“Any program proposed and developed should not be to the detriment of economic growth nor at the expense of other social groups,” Daim said. “Another new area that the council is excited about is a recommendation on improving education for our children, who are the future of our nation. And not just for the Bumiputera, but for all Malaysian children.”

The suggestions from the advisory council were part of a report, completed on Monday, recommending the government review decadeslong policies seen as promoting abuse of power and hampering progress.

The report, Daim said, was a culmination of 100 days of feedback from over 350 individuals at more than 200 organizations, which included regulatory enforcement agencies, trade associations and social activists.

The report proposed a new framework for investment incentives that are “outcome-based,” so that they promote sustainable and inclusive economic growth, he said.

The country’s fiscal position would be strengthened with a revised tax policy, aiming to increase the government coffers after the abolishment of the goods and services tax — a crucial revenue source.

The recommendations, if adopted by the government, would overturn long-held practices.

Critics say Bumiputra, which translates to “sons of the soil,” has led to corruption. Beneficiaries who have won government contracts without an open tender sell their stakes for a quick profit. Those who actually take on a contract become beholden to continuous state support, without which they would not survive in an open market.

Former Prime Minister Najib Razak tried to revise the policy when he took power in 2009, proposing to liberalize the economy to increase competitiveness. But his proposal was immediately slammed by Mahathir.

Now in power for the second time, Mahathir appears to realize how such discriminatory measures based on ethnicity could hinder the country’s stated goal of becoming a developed economy by 2020.

The prime minister, on a five-day official visit to China, lamented over the weekend that Malaysia has fallen behind other countries due to the lack of a “learn and produce” mentality. “In Malaysia, we like to buy and that’s it,” Mahathir said in Beijing on Sunday at a meeting with Malaysian citizens living in China.

But it is not clear whether ethnic Malays, who account for about two-thirds of the country’s population, would accept any revision to the Bumiputra policy. If implemented without a wide consensus, the revision could push the conservatives to throw their support behind the opposition, led by the United Malays National Organization, the party that Mahathir once belonged to.

The UMNO recently formed a loose alliance with the conservative Malaysian Islamic Party, or PAS. Both parties, which advocate the protection of race and religion as ideology, are seeking to challenge the Mahathir-led Pakatan Harapan, or the Alliance of Hope.

The five-person council, set up immediately after Mahathir came into power after the May 9 election, was asked to advise the government on institutional reform and resolving the financial scandal at state fund 1Malaysia Development Berhad.

Other members of the council include Zeti Aziz, the former central bank governor of Malaysia; Hong Kong-based tycoon Robert Kuok; Hassan Marican, the former president of Petroliam Nasional, or Petronas; and Jomo Kwame Sundaram, who served for seven years as the United Nations assistant secretary-general for economic development.

[Source: “Mahathir advisers propose review of Malay privileges to spur economy” published by Nikkei Assian Review]Photo Credits: Ying Xian Wong/Nikkei Assian Review